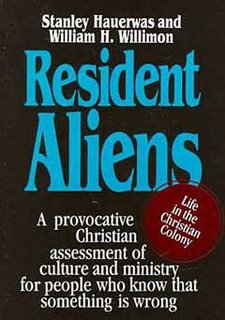

I read Resident Aliens last semester was not initially impressed. But over time, I find myself increasingly drawn to some of its themes.

I read Resident Aliens last semester was not initially impressed. But over time, I find myself increasingly drawn to some of its themes.The title comes from the Anabaptist notion that the Christian community is supposed to live by radically different values than those of the 'world'. That as Christians, we should not be co-opted by the powers that be.

This is the Constantinian Thesis: that the vibrant community of martyring Christians started to die once the Emperor Constantine institutionalized our faith. The purpose of the Church switched to supporting the status quo power structures, rather than supporting only the values of Christ.

I have many disagreements with Hauerwas and Willimon regarding their ideas in this book, but let's not focus on them, rather on the Constantinian Thesis. The authors think that the church in America, until roughly the 1960s, espoused the notion that one was Christian by being born in America and attending church regularly, instead of being Christian by living a Christ-like life. The forces of government (e.g. prayer in schools) and social pressure (e.g. church attendance for sake of social status) supported the Church. But now, since those governmental and social pressures are gone, the Church is left flailing and uncertain about what it means to be a Christian. For generations, the Church preached a watered-down Gospel that was not life- or society-transforming.

I've thought this for a while, but Willimon and Hauerwas put my vague notions into concrete terms. There is no longer a Constantine to back up the Church, and I thank God for it. The Constantian Church preached a Gospel of salvation-by-wearing-a-nice-suit-on-Sundays. Millions of people were inoculated from Christianity as a result and condemned to Hell. Now that the curse of Constantinianism is gone, we can preach an authentic, radical Gospel. The one that Jesus preached.

6 comments:

Lets remember that America is very diverse in her people's faith and backgrounds. But I would have to say that the thought about simply going to church and being a good person is still predominant in many parts of the country...especially the rural areas where I've been.

I agree with Greg's comment. I grew up in a rural community, and Christianity was simply taken for granted as a part of community mores. It was more important to be seen in church every Sunday than to treat others with respect. It was more important to have a favorable opinion of the town's public nativity scene than to reach out to the downtrodden.

What will it take to replace the gospel of Constantine with the gospel of the gospels?

I haven't read Resident Aliens, but I know what I usually think when I hear people bemoaning Constantine. When presented with the opportunity to take responsibility for governance, the church could have said, "No thanks, we'll leave it to the hell-bound pagans. We prefer the purity of powerlessness." The church accepted the responsibility and obviously made some tremendous mistakes along the way, often succumbing to the temptations of power. Even so, if I had it to do all over again, I'd still choose the path of responsibility.

I don't think we can necessarily celebrate the end of constantinian christianity. one only has to look at how our war with terror is sometimes put in "crusade"/holy war terminology by our present adminstration to see the disfunctional marriage of church and empire.

i do however think that hauerwas and willimon hang out in front of us an alternative vision for the church (american church more specifically) that is free to simply be the church and not a partner to empire or the state.

jonathon - Somewhat off topic, but I have NEVER heard the administration describe the present conflict as a holy war to save Christianity or establish its dominance (and I'm in the war business). I've heard the president describe it as a war on terror, on terrorism and on Islamic extremism. For the sake of argument, perhaps the war is unwise, poorly executed or immoral on its face (all positions that some put forth). Even if all that were so, the suggestion that we are fighting it to establish Christian dominance is a figment of someone's imagination (although that's what Islamic extremists trumpet throughout the world).

The American myth sees itself as the land of religious tolerance and peaceful coexistence under God as perceived by the individual, not a Christian empire under In Hoc Signo Vinces. There are problems and unrealities in our myth, too, but they're not the same problems as those of Constantinian dominance.

Back on topic - Constantine and the Christians of his era adopted a poor model for integrating the Christian faith and public life, but it was the only model that they had. In the early 4th century, Christians knew how to be an oppressed minority, not how to be a ruling majority. Romans who did have policital experience also knew how to manipulate, coerce, overpower, deceive and practice hypocrisy. I'm sure that many faithful Christians were just doing the best they could with the circumstances that faced them. Is the power of sin evident in retrospect? Obviously. Would the power of sin be evident 1000 years from now if you suddenly put Jim Wallis and Jim Winkler in charge of the world today? You bet. It's a characteristic of the world in which we live.

John - Sorry for the somewhat long comment.

m lew,

if what i said was that this administration has issued a holy war, please let me say that that's not what i meant, exactly. it's the rhetorical language that is used that implies the crusade/holy war.

with quotes from President Bush such as:

1. "the success of American military and foreign policy is connected to a religiously inspired "mission,""

or

2. "This 'crusade', this war on terrorism is going to take a while....", sept. 16, 2001

is it not the least bit credible to say that our current administration USES religious language somewhat coercively that could be considered "religious empire language"?

and m lew, i wonder if you are in the "war business"? i have often viewed chaplains as symbols and vessals of peace in the midst of conflict. the fact that you asa chaplain do not carry a firearm or participate in war is a symbol of peace in the midst of war. the fact that you council those affected by war and conflict is a testiment to the peace that God intends. i see military chaplains in many ways as the ultimate expression of what it might mean to be a peacemaker.

thank you for being a peacemaker in the midst of those who are in the midst of conflict.

shalom,

jonathon

Post a Comment