Previous contest winner

Previous contest winnerWINNER: John Wilks:

2006 Wookie of the Year

Don't charge the mound- Wookies have been known to pull people's arms out of their sockets.

A Blog of Geek Eccentricities

Previous contest winner

Previous contest winner Today, Katherine and I went to the Blue Star Contemporary Art Center in San Antonio. There, I discovered the work of William Betts. This is 01:58:31 and reflects a body of his work which imitates surveillance cameras. Betts uses proprietary technology to transfer pixels from a digital photograph to dots of acrylic paint onto a canvas, forming a grainy but coherent image. It's machine-made pointillism. Brilliant!

Today, Katherine and I went to the Blue Star Contemporary Art Center in San Antonio. There, I discovered the work of William Betts. This is 01:58:31 and reflects a body of his work which imitates surveillance cameras. Betts uses proprietary technology to transfer pixels from a digital photograph to dots of acrylic paint onto a canvas, forming a grainy but coherent image. It's machine-made pointillism. Brilliant!

This is The Kingdom of Heaven by Evelyn De Morgan.

This is The Kingdom of Heaven by Evelyn De Morgan.

Who Should Paint You: Andy Warhol |

You've got an interested edge that would be reflected in any portrait You don't need any fancy paint techniques to stand out from the crowd! |

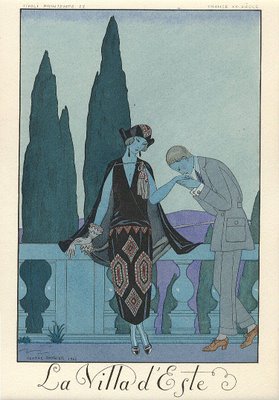

Getting to see so many museums and galleries in the past few days and increasing exposure to the early 20th Century has put me in an Art Deco mood. It is an era that I simply adore, from painting to sculpture to fashion to design -- every element of that era has a simultaneously glamorous but relaxing geometry.

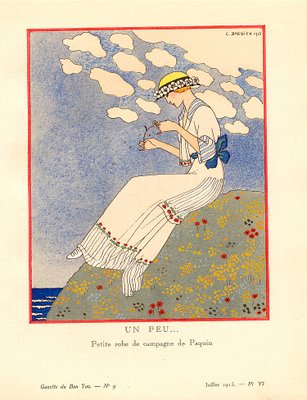

Getting to see so many museums and galleries in the past few days and increasing exposure to the early 20th Century has put me in an Art Deco mood. It is an era that I simply adore, from painting to sculpture to fashion to design -- every element of that era has a simultaneously glamorous but relaxing geometry. Ah, idyll joys of being idle! This is Un Peu (1913). As I've noted before, engaging with art is like taking a mini-vacation away from the troubles of the world. Godward thought along the same lines.

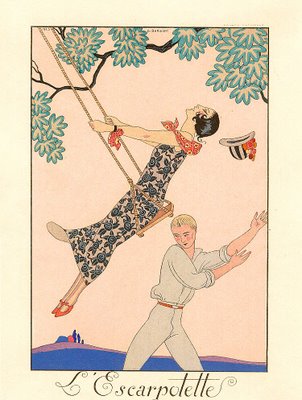

Ah, idyll joys of being idle! This is Un Peu (1913). As I've noted before, engaging with art is like taking a mini-vacation away from the troubles of the world. Godward thought along the same lines. Barbier captured the self-deluded ecstasy of the Roaring Twenties, much like the playful oblivion of the French Rococo period. This is L'Escarpotette (1924).

Barbier captured the self-deluded ecstasy of the Roaring Twenties, much like the playful oblivion of the French Rococo period. This is L'Escarpotette (1924).

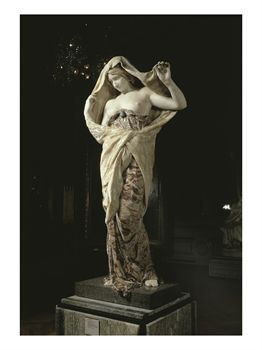

Today, I glanced through the works of Louis-Ernest Barrias (1841-1905), a French Academic and Art Nouveau sculptor. Although his style and training were Academic, it was his subject matter which broke him from Academic norms -- and in a fascinating way.

Today, I glanced through the works of Louis-Ernest Barrias (1841-1905), a French Academic and Art Nouveau sculptor. Although his style and training were Academic, it was his subject matter which broke him from Academic norms -- and in a fascinating way. Electricity, which was at the entrance to the Gallery of Machines at the 1889 Paris Exposition. I don't know where it is now.

Electricity, which was at the entrance to the Gallery of Machines at the 1889 Paris Exposition. I don't know where it is now. Nubian Alligator Hunters (1894), at the Musee D'Orsay.

Nubian Alligator Hunters (1894), at the Musee D'Orsay. This is The Dancing Lesson (1880) by Edgar Degas. The SAMA is currently holding a special exhibit of Impressionists on loan from the Clark Art Institute.

This is The Dancing Lesson (1880) by Edgar Degas. The SAMA is currently holding a special exhibit of Impressionists on loan from the Clark Art Institute. The Onions (1881) by Pierre-Auguste Renoir was also at the special exhibit. Renoir's unique use of light delicately depicts the translucent skins of the onions.

The Onions (1881) by Pierre-Auguste Renoir was also at the special exhibit. Renoir's unique use of light delicately depicts the translucent skins of the onions. At the Concert (1880), also by Renoir, who is by far my favorite impressionist. Renoir was a master of luminescence. This canvas radiated with a warm glow, particularly in the subtly shifting flesh tones. I was also impressed by the roses, which took the forms of whirlpools of reds, pinks, and whites.

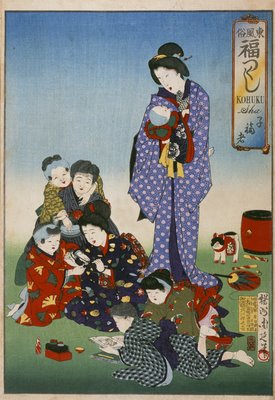

At the Concert (1880), also by Renoir, who is by far my favorite impressionist. Renoir was a master of luminescence. This canvas radiated with a warm glow, particularly in the subtly shifting flesh tones. I was also impressed by the roses, which took the forms of whirlpools of reds, pinks, and whites. There was also a collection of 19th Century Japanese prints in a sideroom. Yoshu Chikanobu was a woodblock printer of the Meiji Period. He usually depicted mythological, historical, or familial scenes. Blessed With Children, like many of his works, were written in response to a perceived threat to traditional Japanese values by Westernization.

There was also a collection of 19th Century Japanese prints in a sideroom. Yoshu Chikanobu was a woodblock printer of the Meiji Period. He usually depicted mythological, historical, or familial scenes. Blessed With Children, like many of his works, were written in response to a perceived threat to traditional Japanese values by Westernization.

On Thursday, I met Methoblogger Dale Tedder at a Panera in Jacksonville.

On Thursday, I met Methoblogger Dale Tedder at a Panera in Jacksonville. Joe Carter as an interesting post comparing the character of George Bailey from It's a Wonderful Life and Howard Roark from The Fountainhead:

Joe Carter as an interesting post comparing the character of George Bailey from It's a Wonderful Life and Howard Roark from The Fountainhead: For instance, Roark lives to create inspiring works of architecture but cannot do so without relying on others. When society fails to appreciate his “genius”, his egotistical purity leads him to engage in a massive destruction of private property. By the end of The Fountainhead Roark is revealed to be an infantile, narcissistic, parasite.

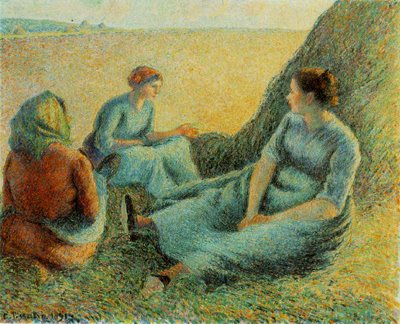

For instance, Roark lives to create inspiring works of architecture but cannot do so without relying on others. When society fails to appreciate his “genius”, his egotistical purity leads him to engage in a massive destruction of private property. By the end of The Fountainhead Roark is revealed to be an infantile, narcissistic, parasite. This is Haymakers Resting (1891) by Camille Pissarro. It is an idealized portrait of rural life. Pissarro was influenced by Neo-Impressionist Seurat's pointillism, which created a shimmering effect across the canvas.

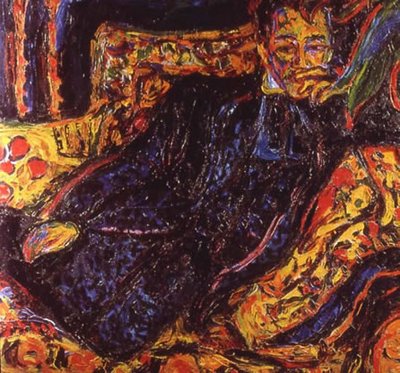

This is Haymakers Resting (1891) by Camille Pissarro. It is an idealized portrait of rural life. Pissarro was influenced by Neo-Impressionist Seurat's pointillism, which created a shimmering effect across the canvas. This is Portrait of Hans Frisch (1907) by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Kirchner was a German Expressionist who conveyed the anxiety of urban life before World War I. He made this painting by squeezing paint from tubes directly onto the canvas and then shaping it with a palette knife.

This is Portrait of Hans Frisch (1907) by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Kirchner was a German Expressionist who conveyed the anxiety of urban life before World War I. He made this painting by squeezing paint from tubes directly onto the canvas and then shaping it with a palette knife. This is War Mother by Charles Umlauf. Umlauf (1911-1994) was a native of Michigan who studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and later taught at the University of Texas. He was an Expressionistic figure sculptor. War Mother, created on the eve of World War II, is an attempt to depict the ghastly suffering of innocent people during war.

This is War Mother by Charles Umlauf. Umlauf (1911-1994) was a native of Michigan who studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and later taught at the University of Texas. He was an Expressionistic figure sculptor. War Mother, created on the eve of World War II, is an attempt to depict the ghastly suffering of innocent people during war. The McNay also had a gilded bronze cast of Philopoemen (1837) by Pierre-Jean David d'Angers. This was one of the handful of Academic pieces in the collection. Philopoemen was a 3rd and 2nd Century B.C. Achaean general who ably defended the Achaean League against vastly larger Spartan, Macedonian, and Roman threats. He was a brutally self-disciplined soldier who eschewed vanity and luxury. Plutarch called him "the last of the Greeks":

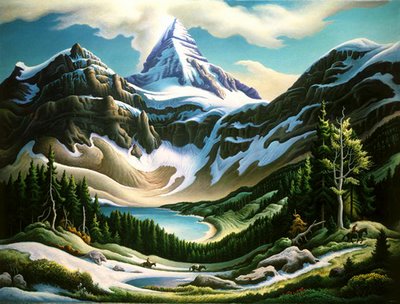

The McNay also had a gilded bronze cast of Philopoemen (1837) by Pierre-Jean David d'Angers. This was one of the handful of Academic pieces in the collection. Philopoemen was a 3rd and 2nd Century B.C. Achaean general who ably defended the Achaean League against vastly larger Spartan, Macedonian, and Roman threats. He was a brutally self-disciplined soldier who eschewed vanity and luxury. Plutarch called him "the last of the Greeks": Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) was an American painter, printmaker, and muralist. He was born in the Ozarks, the son of a Congressman. After dropping out of high school, he studied art in Chicago and Paris, before setting up an atelier in New York City in 1912. He built a successful career and then moved to Kansas City 1941 to become director of the City Art Institute there, remaining the duration of his life. Benton rejected both Academic and Modernist norms for Regionalism -- a 20th Century American movement that celebrated small-town and rural life. This movement, which peaked in the 1930s, reflected American conservativism and nationalism.

Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) was an American painter, printmaker, and muralist. He was born in the Ozarks, the son of a Congressman. After dropping out of high school, he studied art in Chicago and Paris, before setting up an atelier in New York City in 1912. He built a successful career and then moved to Kansas City 1941 to become director of the City Art Institute there, remaining the duration of his life. Benton rejected both Academic and Modernist norms for Regionalism -- a 20th Century American movement that celebrated small-town and rural life. This movement, which peaked in the 1930s, reflected American conservativism and nationalism. The Trail Riders (1964-1965).

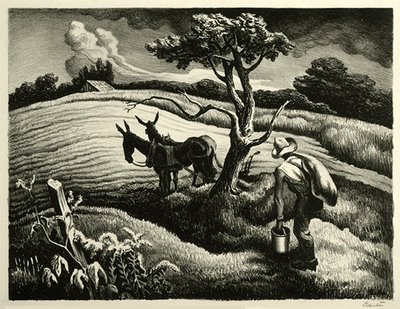

The Trail Riders (1964-1965). Approaching Storm (1938) -- a lithograph.

Approaching Storm (1938) -- a lithograph. Island Hay (1945) -- a lithograph.

Island Hay (1945) -- a lithograph. Previous contest winner

Previous contest winner JD of Proverbs 19:20

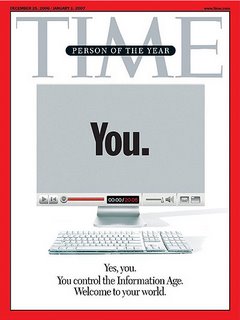

JD of Proverbs 19:20 Time magazine's Person of Year is me. Or you. Something like that.

Time magazine's Person of Year is me. Or you. Something like that.

Hans Makart (1840-1884) was an Austrian Academic painter. He studied in Munich, London, Paris, and Rome. Makart was immensely popular in Vienna, where he built a grand home and atelier. He composed portraits, architectural renderings, but most importantly, huge sprawling works of the the grandiosity that only an empire in its death throws is sufficiently self-deluded enough to embrace. He painted immense canvases from classical themes and courtly life in a way reminiscent of Boucher and French Rococo on the eve of the guillotine's arrival.

Hans Makart (1840-1884) was an Austrian Academic painter. He studied in Munich, London, Paris, and Rome. Makart was immensely popular in Vienna, where he built a grand home and atelier. He composed portraits, architectural renderings, but most importantly, huge sprawling works of the the grandiosity that only an empire in its death throws is sufficiently self-deluded enough to embrace. He painted immense canvases from classical themes and courtly life in a way reminiscent of Boucher and French Rococo on the eve of the guillotine's arrival. The Anniversary Parade: Hunting Party with Treasure Wagon (1879) at the Historical Museum of Stadt Wien in Vienna.

The Anniversary Parade: Hunting Party with Treasure Wagon (1879) at the Historical Museum of Stadt Wien in Vienna. Abundantia -- The Gifts of the Earth. (1870) at the Musee D'Orsay. All of the delightful absurdity of Rococco conveyed through Neoclassical norms.

Abundantia -- The Gifts of the Earth. (1870) at the Musee D'Orsay. All of the delightful absurdity of Rococco conveyed through Neoclassical norms. Snow White Sleeping (1872) also, at the Stadt Wein. Makart was not immune to the revival of European folklore that swept the 19th Century.

Snow White Sleeping (1872) also, at the Stadt Wein. Makart was not immune to the revival of European folklore that swept the 19th Century.

Previous contest winner

Previous contest winner A couple of weeks ago, I sketched out a design for a vehicle appropriate for traversing a zombie-dominated landscape. There were some good comments about my design.

A couple of weeks ago, I sketched out a design for a vehicle appropriate for traversing a zombie-dominated landscape. There were some good comments about my design. My preference is that art remain untained by the ugliness of politics. In the midst of incessant bickering between angry, shouting voices, it would be nice to have a pristine refuge of sanity and peace. Who wants to be perpetually outraged?

My preference is that art remain untained by the ugliness of politics. In the midst of incessant bickering between angry, shouting voices, it would be nice to have a pristine refuge of sanity and peace. Who wants to be perpetually outraged? Follow the example of the Magi:

Follow the example of the Magi: This is the time of year when we think back to the very first Christmas, when the Three Wise Men; Gaspar, Balthazar and Herb, went to see the baby Jesus and, according to the Book of Matthew, "presented unto Him gifts; gold, frankincense, and myrrh."

These are simple words, but if we analyze them carefully, we discover an important, yet often overlooked, theological fact: There is no mention of wrapping paper. If there had been wrapping paper, Matthew would have said so:

"And lo, the gifts were inside 600 square cubits of paper. And the paper was festooned with pictures of Frosty the Snowman. And Joseph was going to throweth it away, but Mary saideth unto him, she saideth, 'Holdeth it! That is nice paper! Saveth it for next year!' And Joseph did rolleth his eyeballs. And the baby Jesus was more interested in the paper than the frankincense."

But these words do not appear in the Bible, which means that the very first Christmas gifts were NOT wrapped. This is because the people giving those gifts had two important characteristics:

1. They were wise.

2. They were men.

Hat tip: Jeff the Baptist

This reminds me of the single most useful thing that I have done in seminary: read The Lost Art of Listening by Michael Nichols. The author advances that people rarely listen to each other and painstakingly details exactly how we fail to listen to other people. I found it to be a big eye-opener. Nichols key message is "Shut up!" Don't interrupt the speaker. Wait.

This reminds me of the single most useful thing that I have done in seminary: read The Lost Art of Listening by Michael Nichols. The author advances that people rarely listen to each other and painstakingly details exactly how we fail to listen to other people. I found it to be a big eye-opener. Nichols key message is "Shut up!" Don't interrupt the speaker. Wait. The secret is out about Brian's quick way of completing grading before the Christmas holidays.

The secret is out about Brian's quick way of completing grading before the Christmas holidays. Previous contest winner

Previous contest winner